A careful reading of the national income accounts suggests that after a strong recovery from the pandemic, there has been a significant ebbing of dynamism over the last three quarters to more modest levels recently, note Arvind Subramanian and Josh Felman.

How is the Indian economy doing? The answer to this question matters to every Indian — and, increasingly, to foreigners as well.

Unfortunately, this issue has become obscured by yet another misguided controversy between the government and its critics.

The former points out that growth accelerated in the last two quarters, reaching 6.1 per cent in the final quarter of the last financial year and 7.8 per cent in the first quarter of FY24, the highest rate for any of the major G20 countries.

The critics claim that this growth wasn’t real, noting that much of the increase in expenditure was attributed to a ‘discrepancy’ rather than standard categories such as investment or consumption. So, is the economy accelerating — or decelerating?

This controversy, like so many, has generated much more heat than light because the critics are not shining a light in the proper place.

After all, we cannot draw conclusions about growth from examining the spending discrepancy because in India gross domestic product (GDP) is not measured from the expenditure side, as the current chief economic advisor has pointed out.

Rather, GDP is measured from the production side, while expenditure figures are instead derived from a mix of measured components and components that are proxied and/or residually allocated.

As a result of these differing approaches, when the government tries to match its figures on production with those on spending, discrepancies inevitably arise. We shouldn’t be upset or even surprised.

So, if we want to understand how the economy is really doing — and whether this is being reflected properly in the headline numbers — we need to look elsewhere.

In particular, we need to look at the production side, especially the nominal numbers, as these are the bedrock data from which all the other figures are calculated.

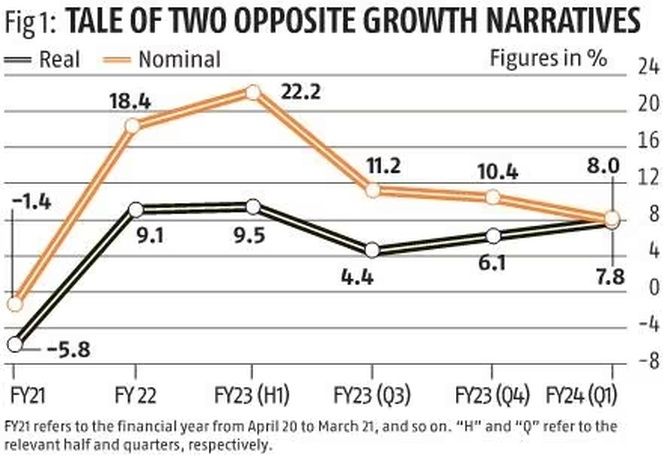

Consider Figure 1, which shows recent trends in GDP growth. The real growth numbers tell an encouraging story.

They show a collapse in the pandemic, followed by a strong recovery which continues through the first half of FY23, a temporary dip and a surge once again.

This is a narrative of a booming India, one that has recovered strongly from the pandemic and is back to about 8 per cent growth.

The story told by the nominal numbers, however, is very different.

The nominal figures track the real numbers until the first half of FY23, but then decline by a whopping 14 percentage points over the past three quarters.

This is a narrative of an economy which has decelerated sharply to very modest levels.

Which narrative is right? At one level, this is an easy question to answer.

Normally, one would just focus on the real numbers, as they show ‘real’ growth, stripping out the illusory effects of inflation. But this assumes that inflation is being measured properly. And unfortunately we cannot make that assumption, since the GDP deflator is not hard data.

It is not measured directly, like the consumer price index (CPI); it is instead a derived number, calculated through a methodology that has well-known problems.

There are two key difficulties, both of which have been discussed extensively in the past few years.

The first is that the Central Statistical Office (CSO) uses single deflation (deflating the nominal value added in each sector by various price indices) rather than the internationally standard technique of double deflation (deflating output by output prices and inputs by input prices).

The failure to use double deflation matters hugely when international prices of critical inputs such as oil move sharply, as they have in recent years because of the pandemic and then Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

The second issue is that a number of sectors of the economy are deflated by inappropriate indices.

In particular, the wholesale price index (WPI) for manufacturing is used to deflate the nominal magnitudes for several non-traded services sectors that account for an important share of total gross value added.

Let’s avoid the gory entrails and instead subject the GDP deflator to a smell test.

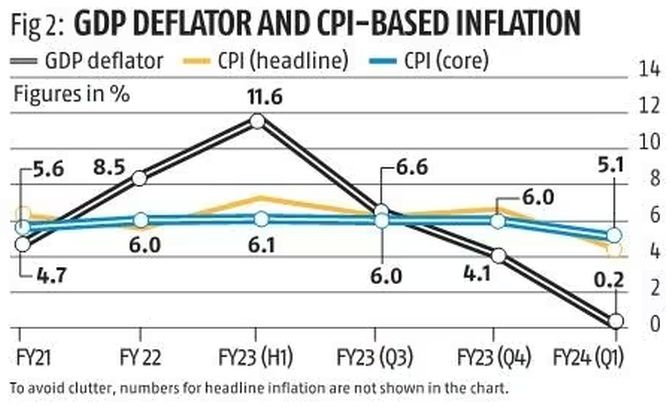

Figure 2 shows that the GDP deflator peaked at 11.6 per cent in the first half of FY23, then collapsed to just 0.2 per cent in the first quarter of FY24.

Does this really correspond to our sense of inflation trends in the economy? Has inflation really been eliminated in recent months?

Certainly, the CPI shows no such thing. Headline CPI-based inflation peaked at 7.2 per cent in the first half of FY23, then eased modestly to 4.6 per cent in the first quarter of FY24.

Core inflation, which strips out volatile food and fuel prices, is even more stable, averaging about 6 per cent throughout the period.

To be clear, the GDP deflator will never be the same as CPI, as the former measures producer prices and the latter consumer prices. But in the other major economies the difference between the two measures has been small and consistent in the post-pandemic period.

In contrast, in India, the difference has been large and fluctuating wildly, swinging from plus 5.1 per cent in the first half of FY23 to minus 4.9 per cent in the first quarter of FY24.

If GDP inflation has actually been much more stable around the levels of CPI-based inflation, then real GDP growth was significantly higher than the headline numbers in FY22 and most of FY23, but substantially lower in the last few quarters, especially in the latest. And this, in turn, would suggest the economy is actually decelerating rapidly.

Can we substantiate this hypothesis from other national income accounts data? Indeed, we can.

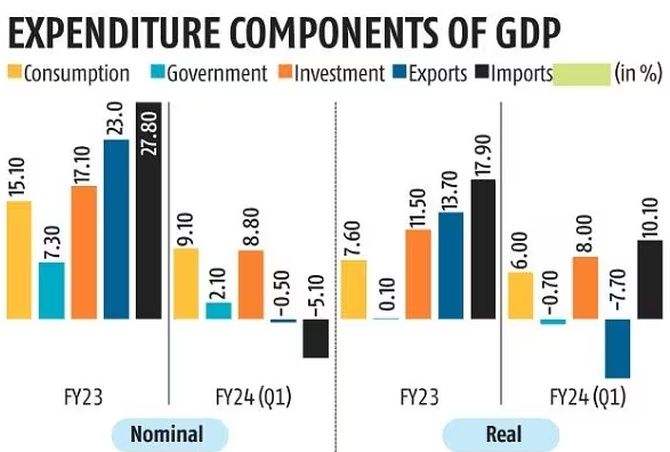

The table above shows that all the components of expenditure decelerated between FY23 and the first quarter of FY24, both when measured in nominal and in real terms.

Note in particular that the key motors of expansion — investment and especially exports — have slowed dramatically.

So have imports, which are another key indicator of the strength of aggregate demand. (Consumption is also important but is not well measured.)

In sum, a careful reading of the national income accounts suggests that after a strong recovery from the pandemic, there has been a significant ebbing of dynamism over the last three quarters to more modest levels recently.

The economy could still get on a trajectory of sustained, rapid growth. But this will require hard work to strengthen policies and institutions.

Policy makers should err on the side of being worried rather than being complacent or triumphalist.

Disclaimer: These are Arvind Subramanian and Josh Felman’s personal views.

Feature Presentation: Rajesh Alva/Rediff.com

Source: Read Full Article