I do have a dream biopic. It has as its subject Renu Saluja, the cosmically gifted editor, with a special focus on the Vidhu Vinod Chopra-Saluja-Sudhir Mishra love story, states Sreehari Nair.

I recently watched a biopic of Muttiah Muralitharan on the back of reading some obituaries of K G George, the great Malayalam film-maker who had passed away just a few weeks earlier.

Like a psychic who sees connections between unconnected events, it struck me that a bad obituary and a bad biopic have a lot in common.

For if a bad obituary does its best to push a deceased legend deeper into the soil, a bad biopic raises a celebrated name to exalted skies.

In both cases you keep looking for some sign that the person being glorified had once walked the face of the earth, and in both cases you are quickly forced to give up on your quest.

Speaking of 800, the Muralitharan biopic, I must tell you that it serves up a roster of everything that’s wrong with our biopics: Predictable beats; too much stress on literal facts as opposed to details; a tendency to over-scale its subject at the expense of everybody else.

In short, there’s enough there to sound that now-trite pronouncement, ‘A hagiography, and nothing more!’

But here’s something to consider: when we demand that our biopics be not hagiographies, what are we asking for exactly?

Though nobody has put it quite this way, I think a good biopic demands that the film-maker be his or her own person rather than a stooge of the subject, be an investigator and not a mere recorder, and occasionally a good biopic demands that the film-maker (if it came to that) be an artist and a murderer.

So bear in mind that when you ask for ‘no hagiographies,’ what you are asking for are not minor tweaks in approach but a whole new way of doing things, a new mindset if you will, a dimension of courage not hitherto explored by the practitioners of this popular genre. And since you would be hard-pressed to find worthy examples to cite from the movies, why not take as your reference one of the great literary biographies of our age?

When Robert Caro started composing his biography of Lyndon Baines Johnson, his ambition wasn’t limited to putting out a cradle-to-grave account of the 36th American president.

Caro wanted to show the reader the nature of political power in America.

The now five-volume biography of LBJ closely follows the trajectory of its subject’s life, but in the process it illuminates everything from how elections are stolen to the kind of levers that are pulled to get a civil rights legislation passed.

Caro’s biography opens up LBJ’s life, but also uses that life as an index to something larger; and it’s fitting that the entire series goes under the title of The Years of Lyndon Johnson.

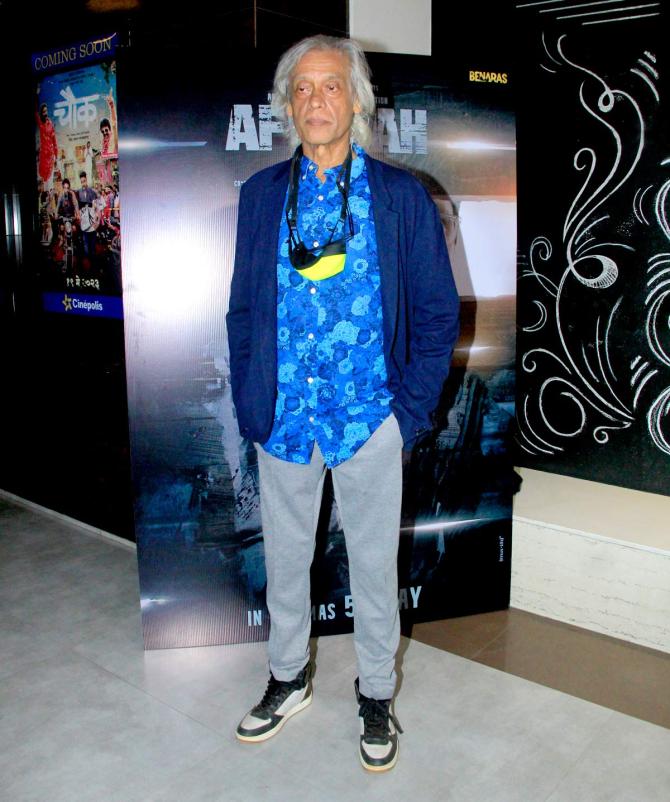

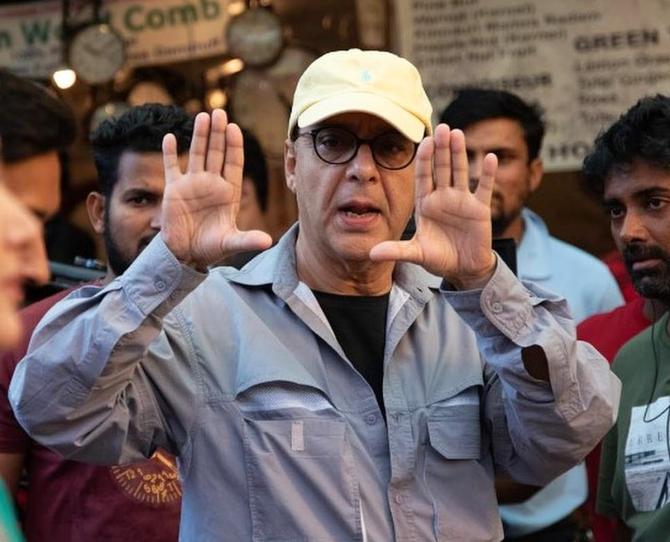

Now, I do have a dream biopic. It has as its subject Renu Saluja, the cosmically gifted editor, with a special focus on the Vidhu Vinod Chopra-Saluja-Sudhir Mishra love story.

From what I know, Chopra and Mishra were thick buddies and leading figures in the Hindi Parallel Cinema movement that took root in the 1980s.

Both men were enamored by the free-spirited and somewhat bohemian Saluja, and the broad outline of their story is sort of like Jules and Jim, only marinated in the Indian spleen: Chopra married Saluja, couldn’t keep her, following which Mishra married her, and for some time the friendship between the two men had morphed into cordial enmity.

Finally, she was diagnosed with cancer, and the old friends (ex-rebels, defunct brats) had come together to care for her in her last days.

This, I tell you, is rich material waiting for a visionary scriptwriter-filmmaker team to come swoop it up.

More importantly perhaps, the life of Renu Saluja provides a clear window into our short-lived parallel cinema movement and its accouterments: The idealism of its players; their phony musings and brashness as they sought to discover their voices; the alcohol and the late-night needs; and shining through all this the editor, the binding glue trying to keep the house together, even as she whipped into shape some of the most distinctive films of that period.

A biopic, then, need not be about the ‘life’ of a subject alone, but about her ‘times’ as well. And when we talk about our biopics as requiring a new mindset, it means approaching our subjects with wider eyes.

Now that’s an honourable pursuit, but here’s the catch. In a country where biopics are aimed at capitalising on the mass hysteria that surrounds a personality, ‘widening your eyes’ would mean ‘facing up to unpleasant truths.’

It is therefore my firm belief that a great biopic will always be wise to the idea that no person who makes it big ever comes out of the experience stain-free.

A great biopic understands that most people who have tasted great success would have to be motivated to the point of madness; which means that they must have walked over corpses, played the art of deception if once in a whil, betrayed their own mentors.

The trick is to love the subject of your biopic while being inherently distrustful of power and the people who wield it.

The bane of every middling biopic is not excessive admiration, it is admiration without scepticism.

Feature Presentation: Rajesh Alva/Rediff.com

Source: Read Full Article